Conceptual Ideas

In this section you will find the following tools:

Perspective Taking

The Iceberg

Theory U

Stock & Flow

Archetypes

Perspective Taking

The Blind Men and the Elephant is an old Indian fable that provides a depiction of how different perspectives must converge for the entire system to be understood. In the fable, each of six blind men approach an elephant in a different place. Each of them touches the elephant to determine what it is and as such, each thinks the object is something different. The one who touches the trunk thinks it is a snake; the one who touches the leg thinks it is a tree; the one who touches the tusk thinks it is a spear, etc. In the fable, the men initially argue adamantly that their belief is correct. It is only when they are able to listen to each other’s perspective and knowledge that they are able to emerge the collective wisdom to understand that it is indeed an elephant.

This is a simple tool that serves as a reminder of the importance of acknowledging the limitation of our own perspective and of integrating a diversity of perspectives before taking any action.

Books

Mind in the Making: The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child Needs Paperback – April 20, 2010, by Ellen Galinsky

Videos

The Blind Men and the Elephant https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wC4ZAnyOQdw

Articles

The Power of Perspective Taking, How leaning in can expand our worldview and deepen our relationships. By Joscelyn Duffy, June 2019

The power of perspective-taking. Being able to step into somebody else’s shoes is an important skill for any leader By Gillian Ku, February 2017

The Iceberg

The iceberg provides a framework for understanding an entire system and reminding us to not focus solely on a particular problem or event, but to dig deeper. In nature, only ten percent of an iceberg can be seen above the water, yet what shapes the iceberg, the water temperature and currents, takes place below the surface, out of sight. This mirrors what often happens in social change efforts where we spend time focusing on what we see (child poverty for example) and not delving deeper to determine the systemic drivers.

About the Iceberg

The Systems Iceberg is a commonly used tool in systems thinking. Its creation is most often credited to American anthropologist, Edward T. Hall, but there are now many variations in regular use. The version that we use in our training wis derived from the work of Mette Boell and Peter Senge.

The iceberg has three levels: symptoms or events; patterns and trends; and structures and processes (which includes both mental models and artefacts).

Level 1: Symptoms or Events

This is the level at which we have the daily experience of issues and challenges. In our example, we would be experiencing children’s challenging behaviour in a classroom. This might involve aggression or withdrawal or running away. At this level of the iceberg, all we can do is react to the behaviour we see. Typically, we respond to this behaviour by applying consequences or seeking extra support for the child. We may be able to temporarily manage the behaviour with some of these solutions, but we are not able to plan for or prevent other incidences of challenging behaviour. The problem endures despite our efforts. This is the level that we are often stuck at when we address complex social or cultural problems, by only addressing symptoms.

Level 2: Patterns or Trends

This is the level just below the surface where we can observe patterns and/or trends in the problems we are facing. In our example, if we considered the incidence of challenging behaviour in classrooms over the last decade, we would see that this behaviour has been steadily increasing. Identifying a pattern or trend allows us to anticipate and to form a plan that is proactive. If we can forecast that there will be children with challenging behaviour arriving in the classroom, we can put additional supports in place and potentially reduce or mitigate the incidence of the challenging behaviour.

Level 3: Structures and Processes

It is at this deepest level of the iceberg that our actions have the potential to recreate or transform the system leading to long term change in outcomes. Structures and processes represent an interaction of both artefacts and mental models. When we consider the fundamental causes of the patterns we observe (in our example of increasing challenging behaviour), you will likely think about an artefact or mental model. Artefacts include: policies, organizational mechanisms; distribution of resources, cultural norms, rules etc. An artefact that might be contributing to the incidence of challenging behaviour could be the way the classroom is organized for example. Hypothetically the set up of the classroom constrains the child, creating stress that leads to difficult behaviour. That would be an artefact that was contributing to an unintended outcome. Mental models include: values, experiences, judgements, beliefs and biases – those deeply held personal ideas about how the world does and should work. A mental model that might contribute to the incidence of challenging behaviour might be our beliefs about what is acceptable behaviour in a classroom. Perhaps we believe that children should speak quietly and not shout. We categorize shouting as “challenging” and set off a whole series of reactions based on that categorization.

Videos

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9I5YvLm5KXI

Articles

Connecting Systems Thinking and Action by Ed Cunliff

Websites

Waters Centre for Systems Thinking https://waterscenterst.org/systems-thinking-tools-and-strategies/tools-strategies/

Books

The Tip of the Iceberg: Managing the Hidden Forces That Can Make or Break Your Organization 1st Edition by Bobby Gombert and David Hutchens

Theory U

Theory U provides points of reference to help us move beyond our habitual way of thinking. It provides a guide for how individuals can make their own contribution to possible solutions that are in tune with what society actually needs. Theory U is about personal leadership and a different way of thinking.

The Theory U process shows how individuals, teams, organizations and large systems can build the essential leadership capacities needed to address the root causes of today’s social, environmental, and spiritual challenges. In essence, we show how to update the operating code in our societal systems through a shift in consciousness from ego-system to eco-system awareness.

Levels of Listening

To work with the Theory U requires courage and the ability to listen deeply. The Levels of Listening approach maps onto the same idea of open mind, open heart and open will. When we listen at level one, we remain in our own heads and we simply reconfirm our existing ideas, biases and habits. When we listen at level 2, we open our minds to receive the perspectives and through of others. When we listen at level 3, we open our hearts toward an empathic atunement with others. When we listen at level 4, we open our whole selves, our will, to what we are hearing and feeling, and we ourselves change as a result of the listening process. To be able to open up new creative and generative spaces with our colleagues, we need to build skills and practices that allow us to operate at level 3 and 4.

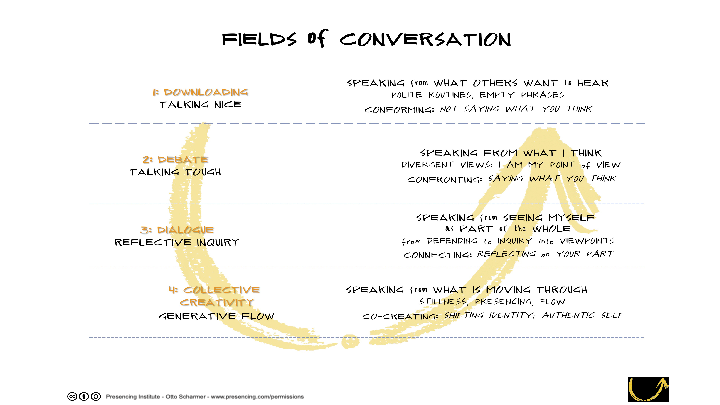

Fields of Conversation

Theory U describes four types/levels of conversations. People relate to each other at different levels of conversational complexity; from polite discussion, through the field of debate , towards more open, reflective dialogue and finally collective and generative space.

In Polite Discussion or “Talking Nice”, people listen from within their own story, but without any self-reflection. They only hear that which confirms our own story and therefore there is only reproduced what is already known. It is about being polite and people not saying what they think.

When Talking Tough or Debating, people start listening to each other and to ideas (including our own ideas) objectively, from the outside. But people say what they think and focus on the differences, which often results in a conflict or a clash.

In Reflexive Dialogue, people listen to themselves reflexively and listen to others empathetically-listening from the inside, subjectively. They start surfacing their own paradigms and assumptions and focus on unity.

At the level of Generative Dialogue, people listen not only from within themselves or from within others, but from the whole system. And when they speak, they speak to generate new understanding, to create new possibilities, to open the possibilities that the collective can focus on an emergent future.

Websites

The Presencing Institute https://www.presencing.org/

Videos

The Ego to Eco Framework https://www.presencing.org/resource/video/the_ego_to_eco_framework_1507660926

Books

Theory U: Leading from the Future as it Emerges 2nd Edition by C. Otto Scharmer, 2016

The Essentials of Theory U: Core Principles and Applications by C. Otto Scharmer, 2018

Presence: An Exploration of Profound Change in People, Organizations, and Society by Peter M. Senge, C. Otto Scharmer, Joseph Jaworski, Betty Sue Flowers, 2004

Stock & Flow Diagrams

These diagrams are core to systems thinking practice. A system stock is a store, or a quantity of a material: something that you want to focus on changing. It may be a quality within a population that we want to address. Stocks change over time through the actions of flows. These flows can be positive - contributing to a positive increase in the stock - or negative - draining or depleting the stock.

Websites

Systems Thinker; https://thesystemsthinker.com/

Academy for Systems Change; http://donellameadows.org/systems-thinking-resources/

Books

Thinking in Systems: A Primer Paperback, December 3, 2008 by Donella H. Meadows (Author), Diana Wright (Editor)

The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization: Second edition by Peter M Senge (6-Apr-2006)

Articles

Step by Step Stocks and Flows: Improving the Rigor of your thinking; Daniel Aronson, Daniel Angelaki

System Archetype: Shifting the Burden

System archetypes are commonly occurring ways that systems behave. They consist of two or more balancing or reinforcing loops. Archetypes can help us explain what has happened over time in a system and can help us predict what will happen in the future if we do not take any action.

image source: system-thinking.org

Shifting the Burden

This archetype usually begins with a problem symptom that prompts someone to intervene and “solve” it. The solution (or solutions) that are obvious and immediately implementable usually relieve the problem symptom very quickly. But these symptomatic solutions divert attention away from the fundamental problem, often making the fundamental solution more difficult to achieve.

Websites

The Systems Thinker, https://thesystemsthinker.com/

Systems and Us, https://systemsandus.com

Academy for Systems Change http://donellameadows.org/systems-thinking-resources/

Waters Center for Systems Thinking https://waterscenterst.org/

Books

The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization: Second edition by Peter M Senge (6-Apr-2006)

Systems Archetype Basics: From Story to Structure Revised Edition by Daniel H. Kim and Virginia Anderson

Articles

Tools for Systems Thinkers: The 12 Recurring Systems Archetypes by Leyla Acaroglu